|

|

|

|

|

Observations Prospect Creek Sydney

Herpetological observations from

Prospect Creek in the

Sydney region of Australia

Photographs by the author Introduction In 2010,

my wife and I spent the months of October, November and December in the Australian province of New South Wales. During that period we stayed with friends who emigrated from Ter-wispel to Australia in 1965 and have now spent more than 45 years in that country.

Our friends live in the Wetherill Park suburb of the city of Fairfield, about 30 km west of Sydney. We chose to visit Australia during the months of October through January because that is when spring starts there and nature is at its most beautiful. Of course we would be looking for reptiles, which are most active during this time. We only searched during

the daytime, leaving nocturnal animals out of the picture. During our stay in Australia, we experienced almost every weather type – extreme heat, but also cold, strong winds, thunderstorms, hail and lots and lots of rain. This region had not seen this

much precipitation in 15 years and large parts of NSW and Queensland were flooded.

Eastern Water Dragon

Eastern Water Dragon

Prospect Creek Prospect Creek runs from the Prospect Reservoir and meanders for 26 km to meet the Georges River, which in turn ends at the ocean near Sydney. Unfortunately, Prospect Creek is very polluted and rumor has it that people dump all their waste, ranging

from household garbage to even animal carcasses, in the creek. As we experienced first-hand, a strong downpour can make the water level in the creek rise as much as two meters. Scraps of plastic high in the trees are testament to how high the generally calm

water can rise. During our stay a brochure was distributed door to door that expressed concern over the pollution levels in Prospect Creek and requested people to partake in clean-ups and volunteer efforts to improve this situation. Our host family did not

hold much hope that anything would come of this and was of the opinion that people in the area are certainly-willing to work, but only if compensated.

“The gentle flowing water of Prospect Creek”

“The gentle flowing water of Prospect Creek”

Several companies, including a large recycling plant, had recently been established in the area and contributed to the pollution levels with wind-blown

paper and plastic. Prospect Creek is lined with a wide walking and biking path. Almost every day we covered a nearly three hour circuit along the creek between the Fairfield and Smithfield areas. It became clear to us pretty early on that even people living

in this area had no idea of the rich rep-tile fauna found in the creek. The symphony of cricket and bird calls emanating from the creek was overwhelming, ranging from the melancholy call of the Australian Raven (Corvus coronoi-des) to the exuberant laugh of

the Laughing Kookaburra (Dacelo novaeguineae). Beautiful birds, such as the Galah (Race albiceps), Sulphur-crested Cockatoo (Cacatua galerita), Australian White Ibis (Treskiornis molucca), Australian Magpie (Cracticus (Gymnorhina) tibicen), Rainbow Lori-keet

(Trichoglossus haematodus) and numerous other species were observed.

The Prospect Creek near Smithfield

The Prospect Creek near Smithfield

Grass Skink

Grass Skink

Grass Skink

Grass Skink

Lizards

SKINKS

Family Scincidae Skinks

are the most adaptable lizards on the Australian continent and more than 300 species occur there. They can be found practically anywhere, in gardens, rain forests and even basking on the tallest mountains. Grass Skink

Without a doubt one of the more common lizards

is the Grass Skink (Lampropholis delicata) with a total length of 9 cm. This brownish-black animal is usually found in gardens, grassland and open woods. Some females display light narrow lateral lines that run from the snout to the groin. During our travels

along the creek these lizards would dart rapidly away from us. They feed on spiders, ants, larvae, centipedes and other small invertebrates. These lizards mate in spring. The female lays two to five eggs several times per year and young hatch in early summer

and fall. The snout-vent length of these hatchlings is about 16 mm. Just like in our Grass Snake (Natrix natrix), sev-eral females may deposit their eggs in a communal nest site and at times more than 400 Grass Skink eggs can be found in one location.

Garden Skink

The

Garden Skink (Lampropholis guichenoti) appears identical to the Grass Skink at first sight. Their size and coloration are similar and they often share the same habitat. The Garden Skink however displays a more bronze-colored dorsum with small dark and light

flecking. A dark stripe runs along each side, from the nose to the hind limbs. This stripe is usually bordered by a narrow band of a lighter coloration. The ventral surfaces are grayish and its head a bright coppery-brown. These animals feed on similar prey

items as the Grass Skink. Mating takes place in early spring and two to four eggs are produced once or twice per season. Eggs may be deposited until late summer. The snout-vent length of the young is ap-proximately 18 mm. Just like in the Grass Skink there

can be communal egg-laying in suitable areas and nests with more than 200 eggs have been reported. These little lizards were observed predomi-nantly on walls and on the head stones in an old cemetery.

Garden Skink

Garden Skink

Fence Skink

The Fence Skink (Cryptoblepharus virgatus) is a lizard that measures 6 to 7 cm and which is often found near human settlements. They are usually seen on old trees, boulders, walls and fences. In 1995 we found these

animals in great numbers on the wooden fences that separate the houses in this area. Unfortunately, most of these wooden fences have now been replaced with sheet metal which caused most of these lizards to relocate. The metal in these new fences becomes very

hot during sunny days and provides only few hiding places. After searching for a long period we man-aged to find some Fence Skinks on old walls and on the tombstones in an old cemetery. The flattened, gray dorsum of these lizards is demarcated by a light lateral

stripe, while the venter is whit-ish. These exceedingly quick animals are very difficult to photograph and usually disappeared rap-idly between and behind tombstones and rocks. In the Sydney area, this species produces two to three clutches of eggs between

October and late January. Their diet consists of insects, spiders, cockroaches, wasps and ants.

The Fence Skink is hard to photograph

The Fence Skink is hard to photograph

Eastern Water Skink

This is a lizard that can attain a larger size than the species mentioned earlier. The Eastern Water Skink (Eulamprus quoyii) can reach a total length of approximately 25 cm. Like most other skinks, this species

typically has smooth scales that shine in the sunlight. This species has a golden to olive-brown dorsum covered with dark spots. A narrow white to yellow stripe extends from the eye to the tail and is bordered below by a dark band. The venter is creamy white.

As is indicated by its common name, these lizards are generally found near water. This exceedingly common liz-ard is live-bearing and gives birth to two to nine young in December or January. Throughout our time in Australia we noticed gravid females of this

species getting bigger and bigger. Their diet is comprised of a variety of invertebrates, but also includes tadpoles and even berries. Some of these animals could be approached to within one meter, but others still fled from as far away as 5 me-ters. Several

dead animals were observed alongside a bike path and many of them were missing part of their tail.

The Eastern Water Skink is a species of lizard that is common around Prospect Creek

The Eastern Water Skink is a species of lizard that is common around Prospect Creek

Barred-sided Skink

The Barred-sided Skink (Eulamprus tenuis) resembles the Eastern Water Skink, but its coloration and biology are different. This lizard is not as closely tied to an aquatic habitat and is generally found some distance

above the ground on tree trunks, fallen logs and boulders. Often they can be seen basking with part of the body protruding from a crevice in bark or a rock. This species is most frequently observed in the early morning and late afternoon. Its coloration varies

from light to dark brown with darker spots. The sides of its body are marked with a viper-like zigzag stripe. Its ven-tral surfaces are cream-colored. The lower jaw is dark brown with transverse white markings. Snout-vent length in this species is on average

7 cm. Like the Eastern Water Skink, this species is also live-bearing. Its litters of two to six young are born in late January. At birth, the total length of the babies is about 6 cm. The Barred-sided Skink feeds on invertebrates, such as spiders, ants, bee-tles,

grasshoppers, insect larvae and pupae. This species is also known to eat fruit and native ber-ries. Although this is considered a rather shy species we did not encounter any problems closely approaching and photographing these lizards.

The Barred-side Skink prefers a drier biotope

The Barred-side Skink prefers a drier biotope

My wife Sjoukje with an Bleu-tongued lizzard

My wife Sjoukje with an Bleu-tongued lizzard

Eastern Blue-tongued Lizard

One of the most frequently researched lizards is the Eastern Blue-tongued Lizard (Tiliqua scin-coides). It is familiar to almost anyone because they are often encountered in gardens. Adults of this species adapt well

to large suburban backyard habitats with plenty of cover. They get accus-tomed to human activity and may remain in the same area for many years. These habitats often provide a myriad of food, such as snails and slugs, but one should use great care when applying

any poisons to combat these invertebrates. Blue-tongue Lizards are usually found under logs, in animal burrows and rock crevices. We observed one or more individuals on almost every trip we took along the creek. Most were seen around 11.00 am during periods

of hazy sunshine. Under these conditions the lizards can be observed basking with their eyes closed approximately 30 cm away from the nearest vegetation cover. These beautiful skinks are easily approached and handled. Their dorsum ranges from silvery-gray

to yellowish-brown with a series of dark crossbands con-tinuing onto the tail. The head is light brown with a dark stripe between the eye and ear opening. Its total length generally is between 40-45 cm. Eastern Blue-tongued Lizards have very short limbs and

a broad and strikingly cobalt-blue tongue that contrasts sharply with the pink interior of the mouth. If threatened, these animals will display the blue tongue to deter predators. On warm eve-nings this species can also be active at night.

Between January and February this species can give birth to between five and twenty young; each measures approximately 15 cm. Unfortunately these harmless animals are often confused with the dangerously

venomous Death Adder (Acanthophis antarcticus) and are accidentally killed because people often do not see their short limbs in grassy vegetation. Even though these are exceedingly calm animals, careless handling can result in a very painful bite - keep in

mind that these lizards are able to crush snail shells with their powerful jaws. We were very surprised to find this species in the cemetery I mentioned earlier - a location where we did not expect to see it.

The Eastern Blue-tongued lizard that is well researched

The Eastern Blue-tongued lizard that is well researched

Family Agamidae

Approximately

60 species of agamids occur in Australia. They display tremendous variation in morphology, coloration and habitat preference. Their body is covered with granular skin and many have spine-like protrusions on the head and neck.

Eastern

Water Dragon

One of the largest and most beautiful lizards that can be found at Prospect Creek is without doubt the Eastern Water Dragon (Physsignathus lesueurii). This

animal occurs there in a high density. They can reach 90 cm in length, although the average size is about 60 cm. The dorsum is gray to olive-gray with dark transverse bands. A dark stripe extends from the eye to the ear opening. The ventral surface is cream-colored,

but can be bright red in males. The head and neck are adorned with a crest of pointed scales. This species inhabits rivers and creeks and is more often heard than seen. At the slightest sign of disturbance they drop from their perch on a high tree limb into

the water below with a loud splash and swim to shore in true crocodile-fashion with their hind limbs adpressed against the tail. These lizards can remain submerged for quite some time. Occasionally it is possible to approach these animals to within about a

meter and a half. They are highly territo-rial and males do not tolerate other males in their vicinity. This is an omnivorous species. The me-nu consists of cicadas and other insects, frogs and lizards (including their own young). While in the water, these

lizards also catch crustaceans and fish. In addition, flowers and fallen fruit, especi-ally figs and berries, are gladly eaten. Females deposit several clutches of eight to twenty parch-ment-shelled eggs in a shallow depression which is then covered with leaves and soil. The juveni-les measure about 15 cm upon hatching. Apart from adults, we observed many juveniles and sub adults. This

large lizard should be handled with care since it can cause painful bite wounds.

The Eastern Water Dragon is one of the most beautiful and largest reptiles along the Prospect Creek

The Eastern Water Dragon is one of the most beautiful and largest reptiles along the Prospect Creek

MONITOR LIZARDS/ GOANNAS

Family Varanidae

Monitor lizards, generally referred to as Goannas in Australia, are well-adapted and highly special-ized lizards found in most parts of the

continent. They are easily recognized by their long neck, well-developed limbs and snake-like, deeply forked tongue. Most monitors are excellent climbers and swimmers. There are approximately 30 monitor species in Australia and 2 occur in the Sydney region.

Lace-monitor

Visiting the daughter of our hosts for a weekend in the town of Glenhaven, located some 30 km from our main stay, brought us a highlight for our trip. In the ’Holland Reserve Park’ we found a Lace-monitor

(Varanus varius), a lizard that can reach a size of two meters. Just like snakes, these large and powerful monitors have a deeply forked tongue that allows them to detect and analyze scents through a well-developed Jacobson’s Organ in the roof of their

mouth. The dorsal surfaces of this lizard are bluish-black with yellowish spots. Its lower surfaces, including the front limbs, are adorned with yellow cross bands. When first spotted, this animal was on the ground, but quickly and noisily ran off through

the leaf litter and into the nearest Eucalyptus tree. It stopped about halfway up the trunk, where the lizard's powerful limbs and claws were clearly visible. We estimated this animal to measure about 150 cm. Adults of this species can reach a weight of 20

kg. All varanids are egg-layers and this species deposits between six and twenty parchment-shelled

eggs in December or early January. Nests are generally located in a decaying log or a burrow, but can be in terrestrial or arbo-real termite mounds as well. Upon hatching, the young measure about 30 cm. During the winter months and other cold periods this

species shows little activity. Their diet con-sists of insects, reptiles, mammals, but also birds and their eggs are taken from trees. This lizard is often observed along roadsides where it feeds on road-killed animals. They are also regularly seen at picnic

sites where they con-sume food scraps discarded by people. Varanids are the only lizards who can greatly enlarge their esophagus by spreading the hyoid apparatus and lowering their mandibles, and are therefore able to consume disproportionately large prey

items. Goannas are among the favorite foods of Australi-a's Aborigine population. The fat of these animals, mixed with other ingredients, is also used to produce a medicinal ointment to treat rheumatoid arthritis.

The Lace-monitor climbs up the

tree with great speed

Lace-monitor

Lace-monitor

SNAKES

Family Elapidae

Approximately 57 species from this family occur in Australia. All are venomous, although two-thirds of these species

pose no danger to humans. It is remarkable that the species that are most commonly observed include all those that are most dangerous, including the Eastern Tiger Snake (Notechis scutatus) and the Eastern Brown Snake (Pseudonaja textilis). Both are considered

to be among the most venomous and deadly snakes in the world. Many of these species restrict their ac-tivity to the night time.

Eastern Brown Snake

Eastern Brown Snake

Eastern Brown Snake The Eastern Brown Snake was observed only once during our vacation. The animal was found basking while it was half concealed by vegetation. It disappeared with lightning speed

before I had an opportunity to obtain decent photographs. This species is regularly seen near human settle-ments, especially on farms where it keeps rodent populations under control. Eastern Brown Snakes also consume reptiles such as skinks, agamas and geckos,

and its menu includes frogs and birds as well. These snakes are usually seen during the day

but may be nocturnal on warm nights. The snake we observed was light brown, but the coloration of this species can be quite variable. This deadly snake can reach a total length of 230 cm, but on average measures about 130 cm. Juveniles tend to have a more vivid coloration and display a pattern of dark narrow bands on the dorsum and a black top of the head.

Some adult animals retain this juvenile pattern although it may fade with age. This snake usually hides under large rocks, in crevices, abandoned animal burrows, fallen logs and under large pieces of debris around homes and farms. It is an adaptable species

that inhabits a variety of habitats. Eastern Brown Snakes lay eggs; their hatchling young measure 23 to

30 cm. This deadly snake can reach a total length of 230 cm, but on average

measures about 130 cm.

In general, every snake will try to avoid contact with a human. If startled, this snake can react quite aggressively and will rear up, hiss loudly, display

its flattened neck and may attempt to bite. Similar to our Adder (Vipera berus), males of this species conduct ritualized courtship dances that consist of flattening the neck and trying to pin the front end of an opponent's body. The winner of this duel will

be allowed to mate. These snakes feed on lizards, small warm-blooded animals and frogs. People would often ask us on our walks what it was that we were looking for. If we mentioned that we were looking for reptiles, people generally discussed snakes. Whenever

we mentioned having seen an Eastern Brown Snake, people would startle and ask on which side of the creek we had observed it. Of course we would always assure them that the snake was seen on the opposite side of the creek. Eventually, these conversations caused

somebody to put up a sign on a clubhouse near the local athletic field with the text: ’Warning Snakes!’

Eastern Brown Snake

Eastern Brown Snake

Red-bellied Black Snake

The Red-bellied Black Snake (Pseudechis porphyriacus) - one of the more common snakes in the Sydney area - was usually seen once or twice on each circuit. It is a beautifully shiny and jet-black snake that at a distance resembles

a wet discarded inner tube from a bicycle tire. Its underside is dull red or pink. Some individuals have a light brown or gray snout. The eyes are black. This spe-cies can reach a maximum size of 250 cm, but on average they are about 125 cm long. Generally

this species disappears with great speed, but when threatened it will spread its neck and hiss loudly. It may exude a pungent substance from its cloaca, just like our Grass Snake does, but all of this defensive behavior is a sham. However, do not attempt to

grab one of these animals because a bite requires immediate medical attention. Although Red-bellied Black Snakes are venomous and their bites can cause fatalities, their venom is generally not considered dangerously toxic. The venom's main properties appear to be necrotic; it causes tissue damage but does not appear to af-fect the central nervous system. Just like in the Eastern Brown Snake, males of this species engage in ritualized combat

to settle territorial disputes. This species is ovoviviparous and has five to twenty young between February and April - each measuring about 20 cm. Upon birth, the young are surrounded by a transparent membrane from which they emerge immediately or within

a short period. This snake consumes a lot of fish (mostly eels), frogs, lizards, an occasional mammal, and snakes such as the dangerous Eastern Tigersnake (Notechis scutatus), Brownsnake, and members of its own species. If many Red-bellied Black Snakes inhabit

a densely populated area there tend to be fewer encounters with the much more dangerous Tiger and Brown Snakes. A large adult Red-bellied Black Snake does not have many natural predators, but juveniles are preyed upon by kookaburras, birds of prey, goannas

and other snakes. We observed this heat-loving snake basking on hot days, usually about a meter from the nearest vegetative cover. As summer progressed and temperatures increased, this species became less frequently seen. It is likely that on very hot days,

these snakes switch to a crepuscular or nocturnal lifestyle. Sometimes we were able to approach to within a few meters, but often they scurried away very rapidly. We noted adults, as well as juve-nile and sub-adult animals. Especially in the northern

province of Queensland, but increasingly in the northern parts of New South Wales, many of these snakes die from eating the highly toxic Cane Toad (Rhinella mari-nus). The toad's poison is usually lethal for most snake species, but pets that happen to bite

one of these amphibians often do not survive this encounter either. This giant toad was once introduced from South America to combat a plague of sugar cane beetles. Since this toad consumes anything that is smaller in size than it, it has turned into a pest

itself.

The Red-bellied Black Snake is a beautiful snake but can be potentially dangerous to man

The Red-bellied Black Snake is a beautiful snake but can be potentially dangerous to man

TURTLES

Family Chelidae

Australia is home to 15 species of aquatic turtles; all members of the family of so-called snake-neck turtles. All

of these turtles have a long neck, but in some species it is elongated very dramati-cally. These turtles cannot withdraw their head underneath their shell as is seen in most turtles (cryptodira), but rather fold the long neck in a sideways S-curve underneath

the edge of the shell (pleurodira). Snake-neck turtles are only found in the southern hemisphere.

The Eastern Snake-necked Turtle turns his long neck sideways under the carapace

The Eastern Snake-necked Turtle turns his long neck sideways under the carapace

Eastern Snake-necked Turtle

Only one species of Snake-necked Turtle, the Eastern Snake-necked Turtle (Chelodina longicol-lis), occurs in the Sydney area. It is a relatively common species there. Eastern Snake-necked

Tur-tles have an extremely elongated neck. During their migration, which takes place during wet weather conditions, they often cover large distances and have been observed crossing pastures, fields and roads. Especially when crossing roads there can be

significant mortality. During a rainy day I encountered one individual that had left the creek and crawled onto a grassy field located two meters above the water level. When I picked up the turtle it excreted a pungent, musky sub-stance from its cloaca, which

amounted to its only defense against me. These turtles can attain a carapace length of 26 cm. They typically have two wart-like protrusions, the so-called barbells, under their chin. These animals prefer standing water, lagoons and swamps. It is not uncommon

in such habitats to see multiple individuals basking together in a sunny spot. Eastern Snake-necked Turtles lay 8-25 hard-shelled eggs on sunless or rainy days between September and December. Eggs are deposited in a nest that is excavated with their hind legs. After the eggs are in place, soil is put back on top and patted down using the turtle’s plastron. The turtle accomplishes this by ex-tending

its legs and raising the whole body off the ground and then rapidly pounding its body down on top of the loose soil that covers the nest. Depending on the temperature the eggs will hatch in about three months. These turtles feed on insects, worms, snails,

freshwater invertebrates, fish and vegetable matter. The young turtles, in turn, are eaten by fish and birds.

Australian turtles are threatened by a variety of predators. These

include native species such as the Dingo (Canis lupus dingo), monitor lizards, the White-tailed Water Rat (Hydromys chrysogaster) and the Australian Raven (Corvus coronoides). However, several introduced species like feral pigs, and Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes)

pose a significant threat as well. In addition, livestock cattle trample the turtle’s nests. Hundreds of turtles are killed annually in so-called ’Yabby Traps’. A Yabby (Cherax destructor) is a crayfish-like animal that is caught with funnel

traps for human consumption. Turtles that are caught in these traps can drown since they can only remain sub-merged for two hours without needing to surface to breathe. A much larger problem for Australian turtles is that in recent years more and more creeks

and marshes dry up. This is often caused by irrigation systems that drain rainwater away from natural wetlands. As a mitigation measure, the water that is withdrawn from nature is sometimes replaced with large amounts of salt ocean water that is pumped into

the wetlands. The influx of sediment and salt kills thousands of reptiles that rely on fresh water.

Eastern Snake-necked Turtles

Eastern Snake-necked Turtles

Cemetery Smithfield

On our way to Prospect Creek we would invariably pass an old, mostly derelict cemetery that ap-parently was still in use. From the road we could always see numerous lizards darting away amongst the headstones and therefore decided to pay

the area a visit. We managed to spend many hours there and decided that we had never observed this much life in a cemetery. The place was full of Fence Skinks that ran between the monuments and tombs, but we also observed Grass Skinks and Garden Skinks. Our

biggest surprise was the discovery of Eastern Blue-tongued Liz-ards. These animals were utilizing uneven headstones that left space beneath them to crawl into. During appropriate weather conditions these lizards would emerge and bask on top of the head-stones.

During one visit we were able to detect no fewer than five adult individuals.

A beautiful colored Blue-tongued Lizard seen in the old cemetery in Smithfield

A beautiful colored Blue-tongued Lizard seen in the old cemetery in Smithfield

In Smithfield cemetery where four species of lizards were found and five Blue-tongued Lizards were seen

In Smithfield cemetery where four species of lizards were found and five Blue-tongued Lizards were seen

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank our

Australian host family Jantje and son Eric Faber, with whom we stayed for three months. We would like to express our gratitude for their hospitality and the lovely time we had with them. They spared no expense to make our stay enjoyable.

We also want to thank our friend Sjoerd Faber for his ever cheerful reception each time we dropped in, exhausted after a long walk. It was always a pleasure to quench our thirst with a large VB

and recount exciting stories from years past.

And last but not least we want to thank Twan Leenders, president/executive director of the Roger Tory Peterson Institute of Natural

History in Jamestown, NY, who was willing to translate this ar-ticle into English for us.

LITERATURE

Cogger, H. C. (1994). Reptiles & Amphibians of Australia.

Ehmann, Harald (1992). Encyclopepedia of Australian

Animals (Reptiles).

Griffiths, K. (1987). Reptiles of the Sydney Region.

Swan, G. (1990). A

Field Guide to the Snakes and Lizards of New South Wales.

A Garden Skink in the old cemetery in Smithfield

A Garden Skink in the old cemetery in Smithfield

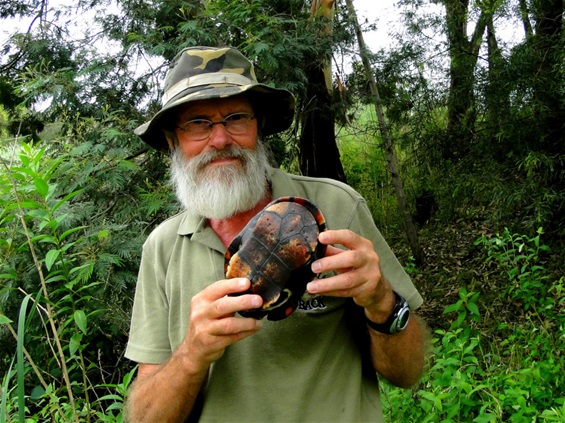

The author at the old cemetery in Smithfield

The author at the old cemetery in Smithfield

The Barred-sided Skink

The Barred-sided Skink

My wife Sjoukje with an Eastern Snake-necked Turtle

My wife Sjoukje with an Eastern Snake-necked Turtle

The author with an Eastern Snake-necked Turtle

The author with an Eastern Snake-necked Turtle

Our visit in 2010 showed Prospect Creek to be seriously polluted

Our visit in 2010 showed Prospect Creek to be seriously polluted

Lace-monitor

Lace-monitor

Young Eastern Water Dragon

Young Eastern Water Dragon

The author with his young fans Calum and Renee Sproull.

Looking for the Lace-monitor in “Holland Reserve Park’ in Glenhaven

The author with his young fans Calum and Renee Sproull.

Looking for the Lace-monitor in “Holland Reserve Park’ in Glenhaven

Left – the wooden fence which is best for the Fence Skink

Right – the modern metal fence that is too hot for the Fence Skink

Left – the wooden fence which is best for the Fence Skink

Right – the modern metal fence that is too hot for the Fence Skink

At the top is a young Eastern Water Dragon and below it is an Eastern Water Skink

At the top is a young Eastern Water Dragon and below it is an Eastern Water Skink

My wife Sjoukje with an Eastern Snake-necked Turtle.

The animal excreted a pungent, musky substance from its cloaca

My wife Sjoukje with an Eastern Snake-necked Turtle.

The animal excreted a pungent, musky substance from its cloaca

Eastern Water Skink

Eastern Water Skink

The Lace monitor

The Lace monitor

Garden Skink

Garden Skink

The Eastern Blue-tongued Lizard

The Eastern Blue-tongued Lizard

The seriously polluted Prospect Creek in 2010

The seriously polluted Prospect Creek in 2010

|

|

|

|

|

|